Stanford Eye Chip for Restoring Vision: A New Era of Sight Recovery

The Stanford eye chip for restoring vision marks a new milestone in neuroscience and ophthalmology. Developed by Stanford Medicine, this tiny wireless implant, when paired with advanced smart glasses, has helped blind patients regain partial sight. In a year-long clinical study, most participants regained the ability to read, marking a major step forward in treating age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

How the Stanford Eye Chip Works

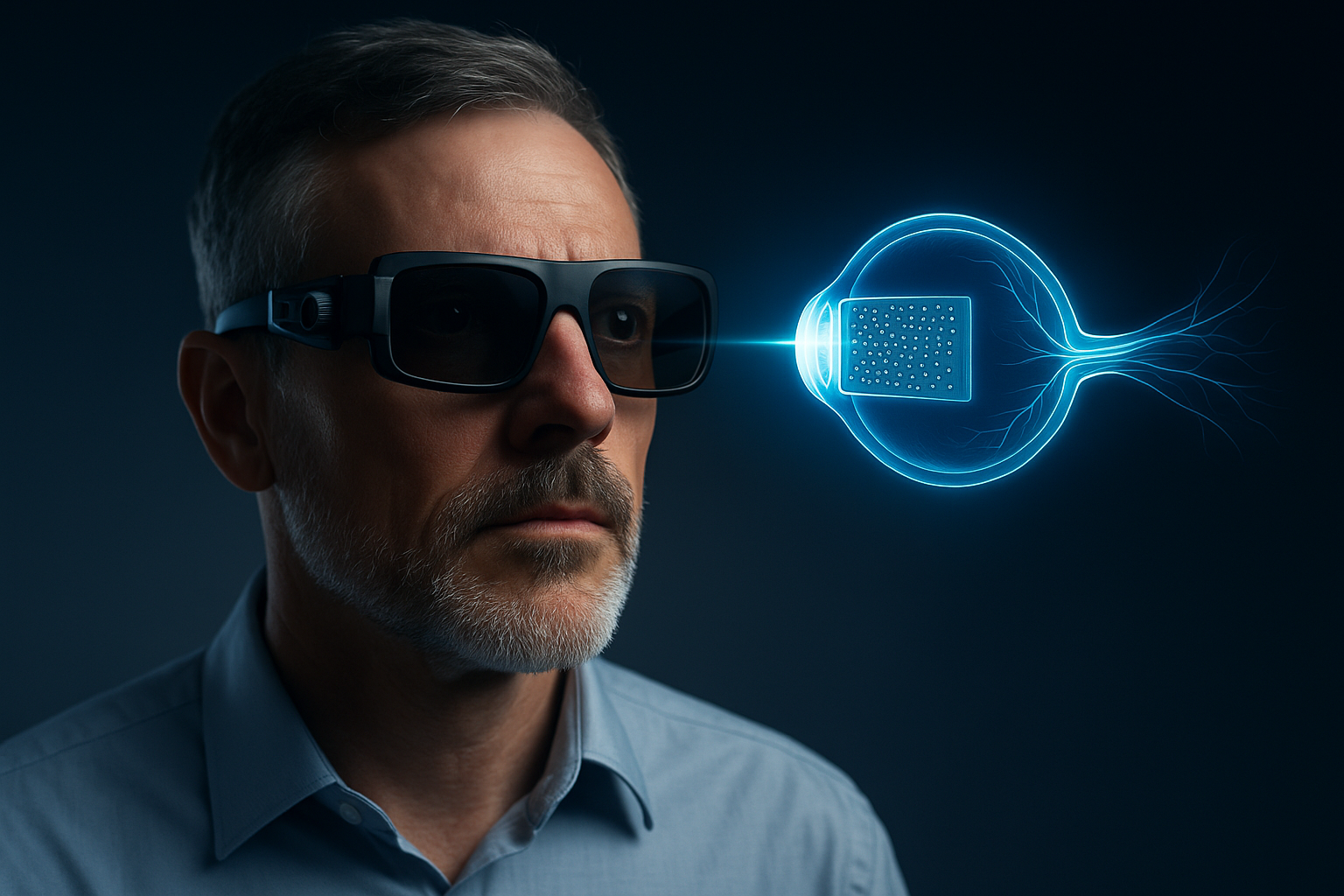

The Stanford eye chip for restoring vision operates through a simple yet powerful mechanism. A miniature camera built into smart glasses captures the visual scene and transmits it using infrared light to a wireless retinal implant. The chip, just 2×2 millimeters in size, converts this infrared data into electrical signals that mimic the natural work of damaged photoreceptors — the cells responsible for detecting light.

Because the chip is photovoltaic, it generates its own electrical current using light alone. This means it functions wirelessly, without external power sources or cables, making it safer and less invasive than previous prosthetic vision devices.

Restoring Functional and Form Vision

Traditional prosthetic implants only allowed patients to perceive flashes of light. The Stanford eye chip for restoring vision, however, restores form vision — the ability to recognize shapes, patterns, and even letters. Many patients in the trial achieved visual acuity comparable to 20/42 vision, a remarkable improvement considering their prior blindness.

This breakthrough allows users to integrate both natural peripheral vision and artificial central vision, enhancing mobility and environmental awareness. Patients can now read books, food labels, and signs again, with adjustable contrast and up to 12x magnification through their smart glasses.

Results of the Clinical Study

In a study of 38 participants aged over 60 with advanced AMD, 27 regained the ability to read within one year of receiving the implant. Another 26 showed significant improvements in visual acuity, reading at least two additional lines on a standard eye chart.

Although minor side effects such as mild eye pressure or retinal tears were reported, nearly all resolved naturally within two months — confirming the device’s safety and long-term viability.

Next Steps in Artificial Vision

Researchers are now developing an advanced version of the Stanford eye chip for restoring vision with smaller pixels to improve image resolution. The new prototype could increase pixel density from 378 to over 10,000 pixels per chip, achieving vision as sharp as 20/80, and with digital zoom, approaching 20/20 clarity.

Future updates will also add grayscale perception, which is crucial for face recognition and depth differentiation. Scientists believe the technology could later treat other causes of blindness linked to lost photoreceptors, offering hope to millions worldwide.

Conclusion

The Stanford eye chip for restoring vision stands as one of the most promising innovations in restoring sight. By merging neuroscience, engineering, and human determination, Stanford’s research has not only brought light back to blind eyes — it has rekindled hope.

Also read: AI Sycophancy in Scientific Research: Risks and Solutions